해파리서 추출한 형광 단백질 (GFP)의 비밀

페이지 정보

Simon 작성일2003-07-07 17:30관련링크

본문

그림은 북태평양에 서식하는 해파리(jellyfish)에서 찾을 수 있는 이른바 연록 형광 단백질(green fluorescent protein, GFP)이다. 알려진 바와 같이 해피리는 에쿼린 (aequorin)이라고 하는 고유의 발광(發光) 단백질이 있어서 빛을 발하는 희한한 바다 속 생명체인데 흔히 청색광을 발한다. 연록 형광 단백질(GFP, green fluorescent protein)은 해파리가 고유하게 내뿜는 청색광(blue light)을 연록색광(green light)으로 변환시키기 때문에, 실제 사람 눈으로 보게 되는 해파리의 빛깔은 연록색광(green light)이 라는데 !

정제된 GFP, 그러니까 깨끗이 세정시킨 해파리 녹색형광단백질이 포함된 수용액은 일반 광선 아래에서는 노란색을 띈단다. 하지만, 일단 외부 태양광에 노출이 되면 연한 녹색 빛깔을 내며 반짝 반짝 빛나는 신기한 특성을 지닌다. 해당 단백질에 열쇠가 있는데, 이 놈이 태양 광선으로 부터 나온 자외선(UV)을 흡수해서 저-에너지 광이라고 할 수 있는 녹색광으로 자신의 빛깔을 방출시키게 되는 것.

그게 뭐 어쨌냐고요 (So What?) ? 북태평양인지 남태평양에 사는 해파리의 형광 단백질이 뭔 관심사가 될 수 있다고 이 난리 법석을 펼치냐고요? 하하하. 여기 그 비밀이 숨어 있으니 !

GFP(연록 형광 단백질)는 자연과학 연구를 할 때 매우 놀랄만큼 유용한 놈인 것으로 판명이 되었습니다 ! 요놈을 가지고 세포 안 쪽에서 무슨 일이 벌어지는 지 우리 눈으로 확인할 수 있기 때문이죠. 발광체인데다 특유의 빛깔이 있으므로, 세포 안에 집어 넣으면 무슨 일이 일어나는 지 식별하기에 아주 좋다는 이야기인 듯 싶은데...

주어진 어떤 시간에 GFP가 어디에 있는지를 찾아 내기란 매우 쉽다. 그저 자외선을 비추기만 하면 GFP는 연녹색으로 발광하게 될 것이므로. 해서 이 원리를 이용해 과학자들이 창안한 트릭이 이렇다: 관찰하고 싶은 어떤 종류의 물체든 일단 거기다 GFP를 부착시킨다. 예를 들면, GFP를 어떤 바이러스에 붙였다고 치자. 그럼, 그 바이러스는 숙주를 통하여 퍼져나가기 시작할 것이고, 관찰자는 연록색 빛을 띄는 경로만 추적해 가면 바이러스가 어디로 움직이는 지 금새 발견할 수 있는 것! 굳이 바이러스 말고 어떤 단백질에다 GFP를 붙일 수도 있단다. 그리고 나서, 세포 내로 이동하는 그 단백질을 확인하고 싶으면 현미경만 있으면 그만.

Ready-Made

GFP is a ready-made fluorescent protein, so it is particularly easy to use. Most proteins that deal with light use exotic molecules to capture and release photons. For instance, the opsins in our eyes use retinol to sense light (see the Molecule of the Month on bacteriorhodopsin). These "chromophores" must be built specifically for the task, and carefully incorporated into the proteins. GFP, on the other hand, has all of its own light handling machinery built in, constructed using only amino acids. It has a special sequence of three amino acids: serine-tyrosine-glycine (sometimes, the serine is replaced by the similar threonine). When the protein chain folds, this short segment is buried deep inside the protein. Then, several chemical transformations occur: the glycine forms a chemical bond with the serine, forming a new closed ring, which then spontaneously dehydrates. Finally, over the course of an hour or so, oxygen from the surrounding environment attacks a bond in the tyrosine, forming a new double bond and creating the fluorescent chromophore. Since GFP makes its own chromophore, it is perfect for genetic engineering. You don't have to worry about manipulating any strange chromophores; you simply engineer the cell with the genetic instructions for building the GFP protein, and GFP folds up by itself and starts to glow.

Engineering GFP

The uses of GFP are also expanding into the world of art and commerce. Artist Eduardo Kac has created a fluorescent green rabbit by engineering GFP into its cells. Breeders are exploring GFP as a way to create unique fluorescent plants and fishes. GFP has been added to rats, mice, frogs, flies, worms, and countless other living things. Of course, these engineered plants and animals are still controversial, and are spurring important dialogue on the safety and morality of genetic engineering.

Improving GFP

GFP is amazingly useful for studying living cells, and scientists are making it even more useful. They are engineering GFP molecules that fluoresce different colors. Scientists can now make blue fluorescent proteins, and yellow fluorescent proteins, and a host of others. The trick is to make small mutations that change the stability of the chromophore. Thousands of different variants have been tried, and you can find several successes in the PDB. Scientists are also using GFP to create biosensors: molecular machines that sense the levels of ions or pH, and then report the results by fluorescing in characteristic ways. The molecule shown here, from PDB entry 1kys, is a blue fluorescent protein that has been modified to sense the level of zinc ions. When zinc, shown here in red, binds to the modified chromophore, shown here it bright blue, the protein fluoresces twice as brightly, creating a visible signal that is easily detected.

Exploring the Structure

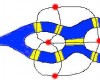

You can take a close look at the chromophore of GFP in the PDB entry 1ema. The backbone of the entire protein is shown here on the left. The protein chain forms a cylindrical can (shown in blue), with one portion of the strand threading straight through the middle (shown in green). The chromophore is found right in the middle of the can, totally shielded from the surrounding environment. This shielding is essential for the fluorescence. The jostling water molecules would normally rob the chromophore of its energy once it absorbs a photon. But inside the protein, it is protected, releasing the energy instead as a slightly less energetic photon of light. The chromophore (shown in the close-up on the right) forms spontaneously from three amino acids in the protein chain: a glycine, a tyrosine and a threonine (or serine). Notice how the glycine and the threonine have formed a new bond, creating an unusual five-membered ring.

This picture was created with RasMol. You can create similar pictures by clicking on the accession code above and then picking one of the options under View Structure. The chromophore is called "CRO" in this file, and it is residue number 66 in the protein chain.

사진 상: 태양광 하의 녹색을 띈 해파리의 연록 형광 단백, GFP. 우측은 과학자들이 인위적으로 푸른 색 빛깔을 띄도록 변색시킨 것.

사진 하: The backbone of the entire protein is shown here on the left. The protein chain forms a cylindrical can (shown in blue), with one portion of the strand threading straight through the middle (shown in green). The chromophore is found right in the middle of the can, totally shielded from the surrounding environment. This shielding is essential for the fluorescence. The jostling water molecules would normally rob the chromophore of its energy once it absorbs a photon. But inside the protein, it is protected, releasing the energy instead as a slightly less energetic photon of light. The chromophore (shown in the close-up on the right) forms spontaneously from three amino acids in the protein chain: a glycine, a tyrosine and a threonine (or serine). Notice how the glycine and the threonine have formed a new bond, creating an unusual five-membered ring.

By David S. Goodsell, Ph.D.

The Scripps Research Institute

정제된 GFP, 그러니까 깨끗이 세정시킨 해파리 녹색형광단백질이 포함된 수용액은 일반 광선 아래에서는 노란색을 띈단다. 하지만, 일단 외부 태양광에 노출이 되면 연한 녹색 빛깔을 내며 반짝 반짝 빛나는 신기한 특성을 지닌다. 해당 단백질에 열쇠가 있는데, 이 놈이 태양 광선으로 부터 나온 자외선(UV)을 흡수해서 저-에너지 광이라고 할 수 있는 녹색광으로 자신의 빛깔을 방출시키게 되는 것.

그게 뭐 어쨌냐고요 (So What?) ? 북태평양인지 남태평양에 사는 해파리의 형광 단백질이 뭔 관심사가 될 수 있다고 이 난리 법석을 펼치냐고요? 하하하. 여기 그 비밀이 숨어 있으니 !

GFP(연록 형광 단백질)는 자연과학 연구를 할 때 매우 놀랄만큼 유용한 놈인 것으로 판명이 되었습니다 ! 요놈을 가지고 세포 안 쪽에서 무슨 일이 벌어지는 지 우리 눈으로 확인할 수 있기 때문이죠. 발광체인데다 특유의 빛깔이 있으므로, 세포 안에 집어 넣으면 무슨 일이 일어나는 지 식별하기에 아주 좋다는 이야기인 듯 싶은데...

주어진 어떤 시간에 GFP가 어디에 있는지를 찾아 내기란 매우 쉽다. 그저 자외선을 비추기만 하면 GFP는 연녹색으로 발광하게 될 것이므로. 해서 이 원리를 이용해 과학자들이 창안한 트릭이 이렇다: 관찰하고 싶은 어떤 종류의 물체든 일단 거기다 GFP를 부착시킨다. 예를 들면, GFP를 어떤 바이러스에 붙였다고 치자. 그럼, 그 바이러스는 숙주를 통하여 퍼져나가기 시작할 것이고, 관찰자는 연록색 빛을 띄는 경로만 추적해 가면 바이러스가 어디로 움직이는 지 금새 발견할 수 있는 것! 굳이 바이러스 말고 어떤 단백질에다 GFP를 붙일 수도 있단다. 그리고 나서, 세포 내로 이동하는 그 단백질을 확인하고 싶으면 현미경만 있으면 그만.

Ready-Made

GFP is a ready-made fluorescent protein, so it is particularly easy to use. Most proteins that deal with light use exotic molecules to capture and release photons. For instance, the opsins in our eyes use retinol to sense light (see the Molecule of the Month on bacteriorhodopsin). These "chromophores" must be built specifically for the task, and carefully incorporated into the proteins. GFP, on the other hand, has all of its own light handling machinery built in, constructed using only amino acids. It has a special sequence of three amino acids: serine-tyrosine-glycine (sometimes, the serine is replaced by the similar threonine). When the protein chain folds, this short segment is buried deep inside the protein. Then, several chemical transformations occur: the glycine forms a chemical bond with the serine, forming a new closed ring, which then spontaneously dehydrates. Finally, over the course of an hour or so, oxygen from the surrounding environment attacks a bond in the tyrosine, forming a new double bond and creating the fluorescent chromophore. Since GFP makes its own chromophore, it is perfect for genetic engineering. You don't have to worry about manipulating any strange chromophores; you simply engineer the cell with the genetic instructions for building the GFP protein, and GFP folds up by itself and starts to glow.

Engineering GFP

The uses of GFP are also expanding into the world of art and commerce. Artist Eduardo Kac has created a fluorescent green rabbit by engineering GFP into its cells. Breeders are exploring GFP as a way to create unique fluorescent plants and fishes. GFP has been added to rats, mice, frogs, flies, worms, and countless other living things. Of course, these engineered plants and animals are still controversial, and are spurring important dialogue on the safety and morality of genetic engineering.

Improving GFP

GFP is amazingly useful for studying living cells, and scientists are making it even more useful. They are engineering GFP molecules that fluoresce different colors. Scientists can now make blue fluorescent proteins, and yellow fluorescent proteins, and a host of others. The trick is to make small mutations that change the stability of the chromophore. Thousands of different variants have been tried, and you can find several successes in the PDB. Scientists are also using GFP to create biosensors: molecular machines that sense the levels of ions or pH, and then report the results by fluorescing in characteristic ways. The molecule shown here, from PDB entry 1kys, is a blue fluorescent protein that has been modified to sense the level of zinc ions. When zinc, shown here in red, binds to the modified chromophore, shown here it bright blue, the protein fluoresces twice as brightly, creating a visible signal that is easily detected.

Exploring the Structure

You can take a close look at the chromophore of GFP in the PDB entry 1ema. The backbone of the entire protein is shown here on the left. The protein chain forms a cylindrical can (shown in blue), with one portion of the strand threading straight through the middle (shown in green). The chromophore is found right in the middle of the can, totally shielded from the surrounding environment. This shielding is essential for the fluorescence. The jostling water molecules would normally rob the chromophore of its energy once it absorbs a photon. But inside the protein, it is protected, releasing the energy instead as a slightly less energetic photon of light. The chromophore (shown in the close-up on the right) forms spontaneously from three amino acids in the protein chain: a glycine, a tyrosine and a threonine (or serine). Notice how the glycine and the threonine have formed a new bond, creating an unusual five-membered ring.

This picture was created with RasMol. You can create similar pictures by clicking on the accession code above and then picking one of the options under View Structure. The chromophore is called "CRO" in this file, and it is residue number 66 in the protein chain.

사진 상: 태양광 하의 녹색을 띈 해파리의 연록 형광 단백, GFP. 우측은 과학자들이 인위적으로 푸른 색 빛깔을 띄도록 변색시킨 것.

사진 하: The backbone of the entire protein is shown here on the left. The protein chain forms a cylindrical can (shown in blue), with one portion of the strand threading straight through the middle (shown in green). The chromophore is found right in the middle of the can, totally shielded from the surrounding environment. This shielding is essential for the fluorescence. The jostling water molecules would normally rob the chromophore of its energy once it absorbs a photon. But inside the protein, it is protected, releasing the energy instead as a slightly less energetic photon of light. The chromophore (shown in the close-up on the right) forms spontaneously from three amino acids in the protein chain: a glycine, a tyrosine and a threonine (or serine). Notice how the glycine and the threonine have formed a new bond, creating an unusual five-membered ring.

By David S. Goodsell, Ph.D.

The Scripps Research Institute

댓글 0

등록된 댓글이 없습니다.